From the author of The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest, and the forthcoming Death’s End comes a story about unborn memories.

First published in Chinese in Sea of Dreams, 2015, a collection of Liu Cixin’s short fiction. Translated by Ken Liu

Mother: Baby, can you hear me?

Fetus: Where am I?

Mother: Oh, good! You can hear me. I’m your mother.

Fetus: Mama! Am I really in your belly? I’m floating in water . . .

Mother: That’s called the ami—ani—amniotic fluid. Hard word, I know. I just learned it today, too.

Fetus: What is this sound? It’s like thunder far away.

Mother: That’s my heartbeat. You’re inside me, remember?

Fetus: I like this place; I want to stay here forever.

Mother: Ha, you can’t do that! You’ve got to be born.

Fetus: No! It’s scary out there.

Mother: Oh . . . we’ll talk more about that later.

Fetus: What’s this line connected to my tummy, Mama?

Mother: That’s your umbilical cord. When you’re inside mommy, you need it to stay alive.

Fetus: Hmmm. Mama, you’ve never been where I am, have you?

Mother: I have! Before I was born, I was inside my mother, too. Except I don’t remember what it was like there, and that’s why you can’t remember, either. Baby, is it dark inside mommy? Can you see anything?

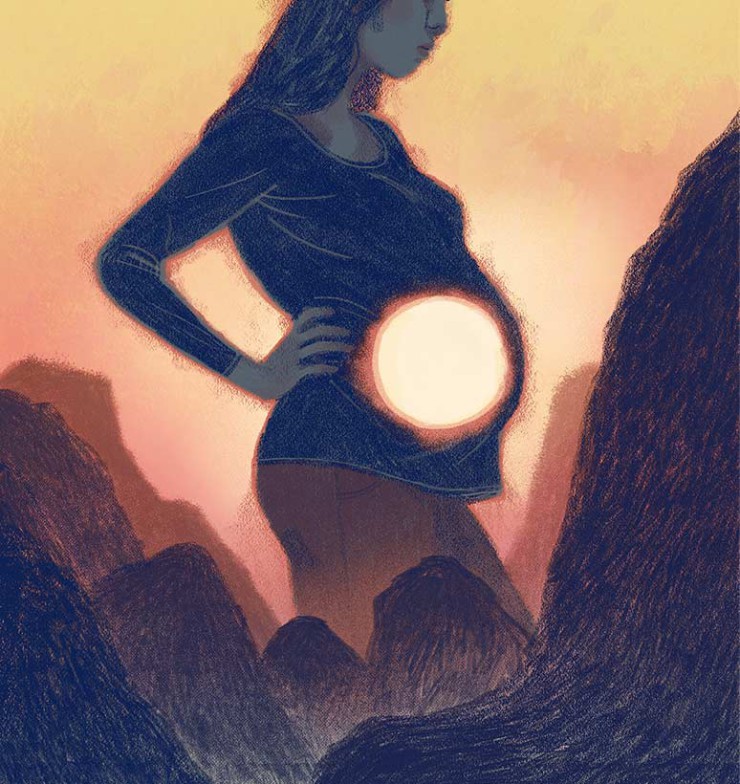

Fetus: There’s a faint light coming from outside. It’s a reddish-orange glow, like the color of the sky when the sun is just setting behind the mountain at Xitao Village.

Mother: You remember Xitao? That’s where I was born! Then you must remember what mommy looks like?

Fetus: I do know what you look like. I even know what you looked like when you were a child. Mama, do you remember the first time you saw yourself?

Mother: Oh, I don’t remember that. I guess it must have been in a mirror? Your grandfather had an old mirror broken into three pieces that he patched back together—

Fetus: No, not that, Mama. You saw yourself for the first time reflected in water.

Mother: Ha-ha . . . I don’t think so. Xitao is in Gansu, land of the Gobi Desert. We were always short of water, and the air was full of dust whipped up by the wind.

Fetus: That’s right. Grandma and Grandpa had to walk kilometers every day to fetch water. One day, just after you turned five, you went with Grandma to the well. On the way back, the sun was high in the sky, and the heat was almost unbearable. You were so thirsty, but you didn’t dare ask for a drink from Grandma’s bucket because you were afraid that she was going to yell at you for not getting enough to drink at the well. But so many villagers had been lined up at the well that a little kid like you couldn’t get past them. It was a drought year, and most of the wells had gone dry. People from all three nearby villages came to that one deep well for their water. . . . Anyway, when Grandma took a break on the way home, you leaned over the side of the bucket to smell the cool water, to feel the moisture against your dry face . . .

Mother: Yes, baby, now I remember!

Fetus: . . .and you saw your reflection in the bucket: your face under a coat of dust, full of sweat streaks like the gullies worn into the loess by rain. . . . That was your first memory of seeing yourself.

Mother: But how can you remember that better than I do?

Fetus: You do remember, Mama; you just can’t call up the memory anymore. But in my mind, all your memories are clear, as clear as though they happened yesterday.

Mother: I don’t know what to say. . . .

Fetus: Mama, I sense someone else out there with you.

Mother: Oh, yes, that’s Dr. Ying. She designed this machine that allows us to talk to each other, even though you can’t really speak while floating in amniotic fluid.

Fetus: I know her! She’s a little bit older than you. She wears glasses and a long white coat.

Mother: Dr. Ying is an amazing person and full of wisdom. She’s a scientist.

Dr. Ying: Hello there!

Fetus: Hello? Um . . . I think you study brains?

Dr. Ying: That’s right. I’m a neuroscientist—that’s someone who studies how brains create thoughts and construct memories. A human brain possesses enormous information storage capacity, with more neurons than there are stars in the Milky Way. But most of the brain’s capacity seems unused. My specialty is studying the parts that lay fallow. We found that the parts of the brain we thought were blank actually hold a huge amount of information. Only recently did we discover that it is memories from our ancestors. Do you understand what I just said, child?

Fetus: I understand some of it. I know you’ve explained this to Mama many times. The parts she understands, I do, too.

Dr. Ying: In fact, memory inheritance is very common across different species. For example, many cognitive patterns we call “instincts”—such as a spider’s knowledge of how to weave a web or a bee’s understanding of how to construct a hive—are really just inherited memories. The newly discovered inheritance of memory in humans is even more complete than in other species. The amount of information involved is too high to be passed down through the genetic code; instead, the memories are coded at the atomic level in the DNA, through quantum states in the atoms. This involves the study of quantum biology—

Mother: Dr. Ying, that’s too complicated for my baby.

Dr. Ying: I’m sorry. I just wanted to let your baby know how lucky he is compared to other children! Although humans possess inherited memories, they usually lie dormant and hidden in the brain. No one has even detected their presence until now.

Mother: Doctor, remember I only went to elementary school. You have to speak simpler.

Fetus: After elementary school, you worked in the fields for a few years, and then you left home to find work.

Mother: Yes, baby, you’re right. I couldn’t stay in Xitao anymore; even the water there tasted bitter. I wanted a different life.

Fetus: You went to several different cities and worked all the jobs migrant laborers did: washing dishes in restaurants; taking care of other people’s babies; making paper boxes in a factory; cooking at a construction site. For a while, when things got really tough, you had to pick through trash for recyclables that you could sell . . .

Mother: Good boy. Keep going. Then what happened?

Fetus: You already know everything I’m telling you!

Mother: Tell the story anyway. Mama likes hearing you talk.

Fetus: You struggled until last year, when you came to Dr. Ying’s lab as a custodian.

Mother: From the start, Dr. Ying liked me. Sometimes, when she came to work early and found me sweeping the halls, she’d stop and chat, asking about my life story. One morning she called me into her office.

Fetus: She asked you, “If you could be born again, where would you rather be born?”

Mother: I answered, “Here, of course! I want to be born in a big city and live a city dweller’s life.”

Fetus: Dr. Ying stared at you for some time and smiled. It was a smile that you didn’t fully understand. Then she said, “If you’re brave, I can make your dream come true.”

Mother: I thought she was joking, but then she explained memory inheritance to me.

Dr. Ying: I told your mother that we had developed a technique to modify the genes in a fertilized egg and activate the dormant inherited memories. If it worked, the next generation would be able to achieve more by building on their inheritance.

Mother: I was stunned, and I asked Dr. Ying, “Do you want me to give birth to a child like that?”

Dr. Ying: I shook my head and told your mother, “You won’t be giving birth to a child; instead, you’ll be giving birth to”—

Fetus: —“to yourself.” That’s what you said.

Mother: I had to think about what she said for a long time before I understood her: If another brain has the exact same memories as yours, then isn’t that person the same as you? But I couldn’t imagine such a baby.

Dr. Ying: I explained to her that it wouldn’t be a baby at all, but an adult in the body of a baby. They’d be able to talk as soon as they were born—or, as we’ve now seen with you, actually before birth; they’d be able to walk and achieve other milestones far faster than ordinary babies; and because they already possessed all the knowledge and experience of an adult, they’d be twenty-plus years ahead of other children developmentally. Of course, we couldn’t be sure that they’d be prodigies, but their descendants would certainly be, because the inherited memories would accumulate generation after generation. After a few generations, memory inheritance would lead to unimaginable miracles! This would be a transformative leap in human civilization, and you, as the pioneering mother in this great endeavor, would be remembered throughout all history.

Mother: And that was how I came to have you, baby.

Fetus: But we don’t know who my father is.

Dr. Ying: For technical reasons, we had to resort to in vitro fertilization. The sperm donor requested that his identity be kept secret, and your mother agreed. In reality, child, his identity isn’t important. Compared to the fathers of other children, your father’s contribution to your life is insignificant, because all your memories are inherited from your mother. We do have the technology to activate the inherited memories of both parents, but out of caution we chose to activate only those from your mother. We don’t know the consequences of having two people’s memories simultaneously active in a single mind.

Mother (heaving a long sigh): You don’t know the consequences of activating just my memories either.

Dr. Ying (after a long silence): That’s true. We don’t know.

Mother: Dr. Ying, I have a question I’ve never dared to ask. . . . You are also young and childless; why didn’t you have a baby like mine?

Fetus: Auntie Ying, Mama thinks you’re very selfish.

Mother: Don’t say that, baby.

Dr. Ying: No, your child is right. It’s fair that you think that; I really am selfish. At the beginning, I did think about having a baby with inherited memories myself, but something gave me pause: We were baffled by the dormant nature of memory inheritance in humans. What was the point of such memories if they weren’t used? Additional research revealed that they were akin to the appendix, an evolutionary vestige. The distant ancestors of modern humans clearly possessed inherited memories that were activated, but over time, such memories became suppressed. We couldn’t explain why evolution would favor the loss of such an important advantage. But nature always has its reasons. There must be some danger that caused these memories to be shut off.

Mother: I don’t blame you for being wary, Dr. Ying. But I participated in this experiment willingly. I want to be born a second time.

Dr. Ying: But you won’t be. From what we know now, you are pregnant not with yourself but a child, a child with all your memories.

Fetus: I agree, Mama. I’m not you, but I can feel that all my memories came from your brain. The only real memories I have are the waters that surround me, your heartbeat, and the faint reddish-orange glow from outside.

Dr. Ying: We made a terrible mistake in thinking that replicating memories was sufficient to replicate a person. A self is composed of many things besides memories, things that cannot be replicated. A person’s memories are like a book, and different readers will experience different feelings. It’s a terrible thing to allow an unborn child to read such a heavy, bleak book.

Mother: It’s true. I like this city, but the city of my memories seems to terrify my baby.

Fetus: The city is frightening! Everything outside is scary, Mama. I don’t want to be born!

Mother: How can you say that? Of course you have to be born.

Fetus: No, Mama! Do you remember the winter mornings in Xitao, when Grandma and Grandpa used to yell at you?

Mother: Of course I remember. My parents used to wake me before the sun was even up so that I could go with them to clean out the sheep pen. I didn’t want to get up at all. It was still dark outside, and the wind sliced across skin like knives. Sometimes it even snowed. I was so warm in my bed, wrapped up in my blanket like an egg in the nest. I always wanted to sleep a little longer.

Fetus: Not just a little longer. You wanted to sleep in the warm blanket forever.

Mother (pausing): Yeah, you’re right.

Fetus: I’m not going out there! Never!

Dr. Ying: I assure you, child, the world outside is not an eternal night in a winter storm. There are days of bright sunshine and spring breeze. Life isn’t easy, but there is much joy and happiness as well.

Mother: Dr. Ying is right! Your mama remembers many happy moments, like the day I left home: When I walked out of Xitao, the sun had just risen. The breeze was cool on my face, and the twittering of many birds filled my ears. I felt like a bird that had just escaped its cage. . . . And that first time after I earned my own money in the city! I walked into the supermarket, and I was filled with bliss, endless possibilities all around me. Can’t you feel my joy, baby?

Fetus: Mama, I remember both of those times very clearly, but they’re horrible memories. The day you left the village, you had to hike thirty kilometers through the mountains to catch a bus in the nearest town. The trail was rough and hard, and you had only sixteen yuan in your pocket; what were you going to do after you had spent them all? Who knew what you were going to find in the world outside? And that supermarket? It was like an ant’s nest, crowded with people pressing on each other. So many strangers, so utterly terrifying . . .

Dr. Ying (after a long silence): I now understand why evolution shut off the activation of inherited memories in humans. As our minds grew ever more sensitive, the ignorance that accompanied our birth was like a warm hut that protected us from the harsh realities of the world. We have taken away your child’s nest and tossed him onto a desolate plain, exposed to the elements.

Fetus: Auntie Ying, what is this line connected to my tummy?

Dr. Ying: I think you already asked your mother that question. That’s your umbilical cord. Before you are born, it provides you with oxygen and nutrients. It’s your lifeline.

A spring morning two years later.

Dr. Ying and the young mother stood side by side in the middle of a public cemetery; the mother held her child in her arms.

“Dr. Ying, did you ever wind up finding what you were looking for?”

“You mean whatever it is, besides memories, that makes a person who they are?” Slowly, Dr. Ying shook her head. “Of course not. I don’t think it’s something that science can find.”

The newly risen sun reflected off the gravestones around them. Countless lives that had already ended glowed again with a soft orange light.

“Tell me where is fancy bred, or in the heart, or in the head?” muttered Dr. Ying.

“What did you say?” The mother looked at Dr. Ying, confused.

“Something Shakespeare once wrote.” Dr. Ying held out her arms, and the mother handed the baby to her.

This wasn’t the baby whose inherited memories had been activated. The young mother had married a technician at the lab, and this was their child.

The fetus who had possessed all his mother’s memories had torn off his umbilical cord a few hours after their conversation. By the time the attending physician realized what had happened, the unborn life was already over. Afterward, everyone was puzzled how his little hands had the strength to accomplish such a thing.

The two women now stood before the grave of the youngest suicide in the history of the human race.

Dr. Ying studied the baby in her arms as though looking at an experiment. But the baby’s gaze was different from hers. He was busy sticking out his little arms to grab at the drifting cottony poplar catkins. Surprise and joy filled his bright, black eyes. The world was a blooming flower, a beautiful, gigantic toy. He was completely unprepared for the long, winding road of life ahead of him, and thus ready for anything.

The two women walked along the path between the gravestones. At the edge of the cemetery, the young mother took her baby back from Dr. Ying.

“It’s time for us to be on our way,” she said, her eyes sparkling with excitement and love.

“The Weight of Memories” copyright © 2016 by Cixin Liu and Ken Liu

Art copyright © 2016 by Richie Pope